The depth of Russia’s expansionist attitudes manifest by Vladimir Putin’s ordered invasion of Ukraine in February of this year has for many, including myself, come as a shock. In listening to the rhetoric coming out of Moscow and studying more in depth and thinking about more deeply the history of Russian chauvinism over the last hundred plus years, perhaps it all makes more sense.

The collapse of Tsarist Russia in the spring of 1917 and then the seizure of the Russian state by the Bolsheviks in the fall of 1917 brought about a surge of optimism amongst some Russians that Russia had an opportunity to throw off centuries of “backwardness” and take its rightful place as a great and powerful nation. In the early decades of the Russian dominated Soviet Union the country’s Bolshevik leaders held tightly to the correctness of Marxism as elaborated by Vladmir Lenin. The Old Bolsheviks’ zealous faith rivaled the leaders of the early Muslim Conquests and the medieval Christian Crusaders. Theirs was an ideology of undeniable destiny. Until it wasn’t.

During the interwar period, from 1919 to 1939, the Soviet leadership under the despot Joseph Stalin was responsible for untold numbers of deaths of their own citizens. Internal deportations to Siberia and elsewhere affected millions of Soviet citizens, particularly ethnic minorities, and killed hundreds of thousands. Stalin’s policy of forced collectivization from 1932 to 1933 caused the deaths by famine of 5 to 7 million Soviet citizens, including over 3 million ethnic Ukrainians. In the late 1930’s hundreds of thousands more Soviet citizens died during Stalin’s reign of terror, including the Great Purge of 1937. During the late 1930’s some of the most famous Old Bolsheviks were arrested, tried and executed on the orders of their old comrade Stalin.

In 1939 Stalin and arguably his most loyal henchman, Vyacheslav Molotov, signed the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact with Nazi Dictator Adolph Hitler and the Nazi Minister of Foreign Affairs, Joachim von Ribbentrop. This Pact called for Nazi Germany to attacked Poland from the west and the Soviets to attack from the east. Nazi Germany invaded Poland on September 1, 1939 with the Soviet following suit and invading from the west on September 17. By early October Poland effectively ceased to exist as a country. Once in control of eastern Poland the Soviets gathered roughly 22,000 Polish officers and other prominent Polish citizens who they had captured during their invasion and executed them in what is commonly referred to as the Katyn Forest Massacre. Stalin wanted these men dead to help ensure that Poland would not revolt under Soviet rule.

The collaboration between Nazi Germany and the Russian dominated Soviet Union only ended when Hitler turned on his ally Stalin and attacked the Soviet Union on June 22, 1941. Prior to that the Soviets supplied the Nazis the raw materials they needed to feed Germany’s war machine in exchange for the Nazis supplying the Soviets with machine tools and other manufactured goods necessary for the Soviet’s war machine. The historical evidence suggests that the main reason for the German invasion of the Soviet Union was a failure of the two dictators, Stalin and Hitler, to mutually agree upon the further forceable division between themselves of Eastern and Southern Europe. Russia’s desire to expand west ran up against Germany’s desire to expand east.

France and Britain declared war upon Nazi Germany after Hitler’s invasion of Poland. Not so the Soviet Union. In fact up until the German attack upon the Soviet Union the British sought to get Stalin to agree to form an alliance with Britain against Germany. Only with Germany’s invasion of their own territory did the Soviet Union join with Britain in the battle against fascism. With the Japanese attack upon Pearl Harbor the United States also declared war against Germany and the tide was turned against Hitler.

What happened to the leaders of Nazi Germany at the end of World War II? What happened to the leaders of the Soviet Union? Their fates explain a lot about the attitudes of both the Germans and the Russians, and their leaders, as to expansionist policies today.

Germany was utterly and completely defeated at the end of the war. The fate of the most prominent leaders of Nazi Germany was ignominious at best. The Nazi Dictator, Adolph Hitler, shot himself in the head on April 30, 1945 as Soviet troops closed in on him in his bunker in Berlin. Herr Fuhrer’s body was then dosed with gasoline and burned beyond recognition.

A day later, one of Hitler’s most loyal followers and the Chief propagandist of the Nazi Party, Joseph Goebbels, committed suicide with his wife shortly after killing his six young children, all by potassium cyanide.

Martin Borman, Hitler’s private secretary and head of the Nazi Party Chancellery, the head office of the Nazi Party, was killed while trying to flee Berlin. His body was not conclusively identified by DNA until 1998.

Heinrich Himmler, one of the main architects of the Holocaust and head of the Nazi Schutstaffel, the notorious SS, was captured while trying to flee Germany. At first he passed himself off as a low level German soldier. When his true identity was discovered while in the custody of the British he too committed suicide by ingesting a cyanide pill.

Others were captured by the allies and prosecuted at the Nuremberg Trials, which ended on October 1, 1946. Hermann Göring, President of the German Reichstag and Commander-in-chief of the Luftwaffe, or Germany Air Force, during the war, was convicted and sentenced to be hanged. The day before he was to be hung he too committed suicide by taking a cyanide pill.

Joachim von Ribbentrop, the Nazi Minister of Foreign Affairs from 1938 to 1945, the man who had negotiated on Hilter’s behalf with Stalin and Molotov for the dismemberment of Poland, was also convicted. Ribbentrop was the first Nazi leader to die by hanging on October 16, 1946.

A few Nazi prominent Nazi officials escaped the gallows. Albert Speer, a German Architect, a favorite of Hitler, and the Nazi Minister of Armaments and War Production, spent 20 years in prison and was released on October 1, 1966. He died on September 1, 1981, one of the very few prominent Nazis to die of natural causes.

Another captured Nazi to escape execution was Rudolph Hess. Hess was Hitler’s Deputy Fuhrer and assisted Hitler in writing his virulently anti-Semitic memoir, Mein Kampf, while both were imprisoned for an attempted coup in 1923. In May of 1941 Hess flew an unauthorized mission to England to try to negotiate some sort of alliance between England and Nazi Germany against the Soviet Union. He was captured, convicted at Nuremberg, and given a life sentence. Hess hung himself while still held at Spandau Prison, the last remaining inmate, on August 17, 1987 at the age of 93.

Those were the fates of the prominent Nazis that precipitated World War II. But what happened to Old Bolsheviks and other leaders of the Soviet Union, who allied themselves with Hitler to initiate the war?

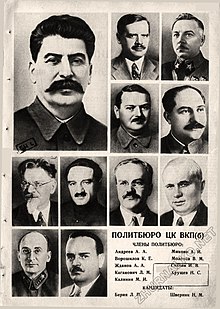

Large photo upper left: Joseph Stalin

Top row left to right: Andrey Andreyev, Kliment Voroshilov

Second row, left to right: Andrei Zhdanov, Lazar Kaganovich

Third row, left to right: Mikhail Kalinin, Anastas Mikoyan, Vyacheslav Molotov, Nikita Khrushchev

Bottom row, left to right: Lavrentiy Beria, Nikolai Bulganin

Joseph Stalin died on March 5, 1953, of a cerebral hemorrhage. The man who was undeniably the driving force behind the deaths of the untold millions mentioned above was still the unquestioned leader of the Soviet Union after the war.

Vyacheslav Molotov, Stalin’s second in command during the war and the man who gave his name to the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact, the man who had served Stalin with unswerving loyalty through decades of Stalin’s tyranny, died in retirement in 1986 at the age of 96.

Lazar Kaganovich, another of Stalin’s most loyal henchmen, who helped plan and implement Stalin’s forced collectivization of peasant farmers that lead to the death by starvation of millions, died in retirement at the age of 97 in 1991.

Kliment Voroshilov, a long time, albeit rather incompetent, Soviet military leader who survived the Great Purge of the late 1930’s because of his intense loyalty to Stalin, died in retirement in 1969 at the age of 88.

Anastas Mikoyan, an Old Bolshevik functionary that who proved his loyalty by signing “death” lists during the Great Purge, died in retirement in 1978 at the age of 82.

Mikhail Kalinin, an Old Bolshevik who was the titular head of the Soviet Union during World War II but who had little real power, died of cancer shortly after retiring in 1946 at the age of 70.

Nikita Khrushchev, who rose to be one of Stalin’s favorites under the tutelage of Lazar Kaganovich, won out in a power struggle to succeed the deceased Stalin as leader of the Soviet Union. Shortly after gaining power Khrushchev denounced the deceased Dictator even though while Stalin lived Khrushchev loyally performed all assigned tasks, including accompanying invading Soviet troops into Poland in September 1939. Khrushchev died of natural causes in 1971 at the age of 77.

One of the few prominent Soviet leaders under Stalin during World War II to meet an early death was Lavrentiy Beria. Beria was head of the Soviet secret police, or NKVD, and one of the driving forces behind the Katyn Forest Massacre of the Polish officers and intelligentsia in 1940. Beria survived Stalin and even maneuvered to be his successor, but he was ultimately blindsided by Khrushchev and his allies. Beria was arrested and in quick succession tried and executed by a bullet through his forehead in 1953. He was 54 years old.

Based on Beria’s proposal, six members of the Soviet Politburo signed the order to execute the Polish officers and intelligentsia in the so-called Katyn Forrest Massacre; Joseph Stalin, Vyacheslav Molotov, Lazar Kaganovich, Kliment Voroshilov, Anastas Mikoyan, and Mikhail Kalinin.

At the Nuremburg trials, the four prosecutors from the United States, Great Britain, France, and the Soviet Union tried the captured Nazi leaders. Without going into the legal complexities, the overall charge against the Nazi defendants was that Nazi Germany conducted a “war of aggression.” The jurisdiction of the court began on September 1, 1939, the day Hitler’s ordered the invasion of Poland began. The great irony of the Nuremburg trials was that the Nazi German leaders under Adolph Hitler were being prosecuted for doing precisely what the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact signed with the Soviet Union under Joseph Stalin called for, the invasion and dismemberment of Poland. Not only that, the Soviets committed exactly the same crime when Stalin invaded Poland on September 17, 1939. In addition, the Soviet executed Polish prisoners of war and civilians at the Katyn Forest and committed atrocities elsewhere just as the Nazis had throughout Europe and on Soviet territory.

I think its very true that the Nazis’ crimes against civilians, if we use as a beginning date September 1, 1939, and go to the end of the war, particularly in the systematic slaughter of people of Jewish descent, outweighs what the Soviets did during that same time frame. But if we add to the ledger of slaughter of Stalin and the Soviets those killed in the 1920’s and 1930’s through the extreme excesses of collectivization, dekulakization, and Stalin’s repeated purges, the essential difference in the balance of evil between Hitler’s Nazi Germany and Stalin’s Soviet Union is one of method and ideology, not one in the amount of pure human suffering caused.

Added to the irony of Nuremberg is that the Soviet Union’s main prosecutor was a man named Roman Rudenko. Rudenko had prosecuted for the Soviets 16 leaders of the Polish Underground, in part for being Nazi collaborators, right after the end of the war in the infamous “Trial of the Sixteen.” In other words, the Soviets collaborated with the Nazis to dismember Poland and then prosecuted the Poles who went underground to fight for their country for being Nazi collaborators. Soviet preparation for the trials at Nuremburg was done by Andrey Vyshinsky. Vyshinsky prosecuted most of Stalin’s show trials in the late 1930’s against Stalin’s perceived Old Bolshevik enemies, men such as Lev Kamenev and Grigory Zinoviev. The show trials Vyshinsky prosecuted were noteworthy for a total absence of due process and absolute assurance that the defendants would be found guilty, and usually executed.

No one should mourn the fates of the Nazis who were tried at Nuremburg. The Nazis committed unspeakable crimes before and during World War II and the nature of those crimes looks no better the deeper into the history one digs. The fact, though, that the equally malevolent Soviets not only escaped judgment but sat in judgment of their one time ally was a huge historical injustice.

At the end of World War II the German people saw their country defeated and the Nazi leadership dead, incarcerated, or in hiding. Germany itself was divided into East Germany and West German, and the capital of Berlin was bombed out and divided into East and West as well. I visited Berlin in 1993, a few years after reunification. In the middle of the city was a church that had been bombed out during the war, sitting in ruins as if to testify of the destruction that befell the city because of Nazi expansionism. Many government buildings had been left with bullet holes and bomb damage clearly visible as a reminder of what the war wrought. The next generation of Germans knew not to believe the siren song of expansionist demagogues. Germany, France, Great Britain, and the other countries of western Europe have now had over 75 years without military conflict between them, this after centuries of some of the most brutal military conflicts in history. Nazi Germany’s defeat brought peace to Germany and the country’s neighbors.

And what of Russia? Many believed that the dissolution of the Soviet Union and the collapse of the Warsaw Pact would mean the end of Russian expansionism. Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in 2014 was a hint that Russian expansionism was not dead. With Vladimir Putin’s ordered Russian invasion of Ukraine this year, and their conduct of the war and rhetoric, we all know for a certainty that Russian expansionism is alive and well. Russia’s grand “Victory Day” parades in celebration in their defeat of Nazi Germany in their “Great Patriotic War” reflects the lessons unlearned from World War II.

The German people and their leaders learned from the fate that befell them at the end of World War II. Moscow’s present leader has demonstrated that he certainly has not. When this latest example of Russian expansionism ends, Russia and the country’s leaders must be brought to some sort of justice, and the expansionist dream ended. Or we will all just be awaiting the next manifestation of the Russian dream of expansion.