Writing about issues of “race” is fraught with landmines and inevitably some people will be insulted no matter what you write. With that said, I think its important to have the conversation even though it can be difficult. Sometimes the most difficult conversations are the most important to have. So here are a few of my thoughts.

During Christmas vacation when I was in first grade my family moved from Northfield Ohio to Bratenahl Ohio, a small suburb of at most a few thousand nestled between Cleveland and Lake Erie. Cleveland in the late 1960’s and early 1970’s was beset by a lot of the same issues confronting many other urban areas in the United States at that time. Particularly troubling in Cleveland was the racial segregation of Cleveland’s neighborhoods, which was pronounced even for the time. Cleveland and Chicago where the two most segregated urban areas in the country. When we moved to Bratenahl it was about 99% White and Cleveland’s Glenville neighborhood just on the other side of I-90 and the railroad tracks was about 99% Black.

During my first day in the first grade at Bratenahl Elementary School, I met the first Black person I ever remember meeting. He was the only Black child in my class at the time and the teacher asked him to show me where my locker was downstairs. I may have met Black people before, but I have a distinct memory of meeting this classmate of mine. This everyday interaction must have been significant because it made a real impression on my young mind.

Bratenahl’s school system, at the time, was the subject of a series of lawsuits seeking to force a merger with the Cleveland Public School System. To forestall that merger, Bratenahl schools gave a number of students from Glenville free tuition to attend Bratenahl’s schools. The one Black student in my class was one of those students from Glenville. He was definitely “the other.”

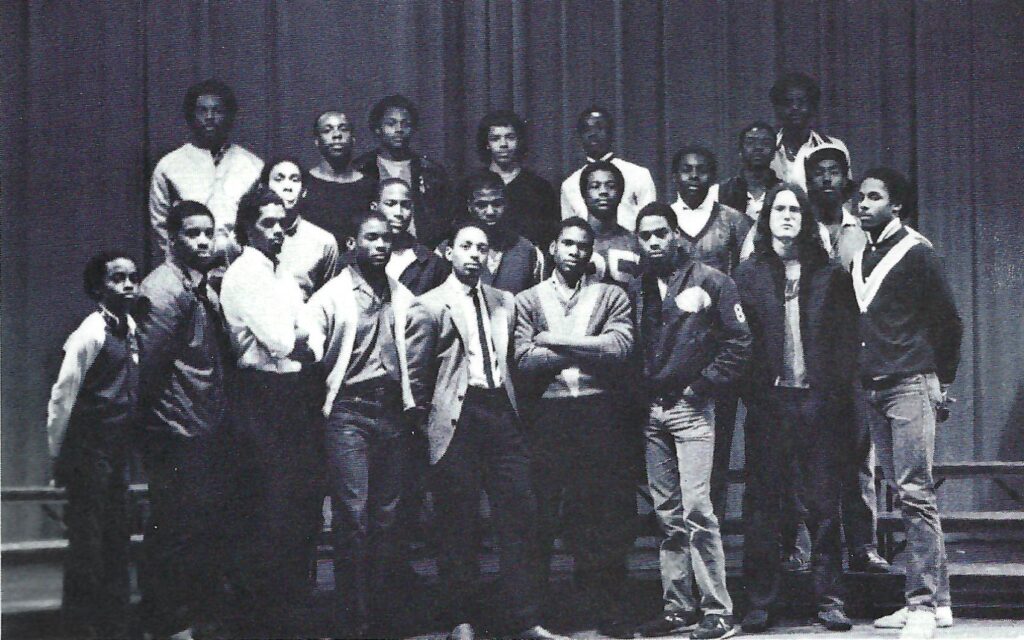

Over the years the lawsuit progressed and more and more students from Glenville were added to Bratenahl’s rolls. Bratenahl’s schools were finally merged with Cleveland’s after my sophomore year at Bratenahl High School. At the time, the high school had about 50 students in four grades, almost equally split between White kids from Bratenahl and Black kids from Glenville and other Cleveland neighborhoods. I wouldn’t say there were no racial issues between students at Bratenahl High School, but they were minimal compared to many urban schools, at least in my mind. I don’t know what others would say. I was the only White boy in my class when the school closed and felt no racial animosity from the Black students or toward the Black students.

My Junior year I attended Collinwood High School in Cleveland. Collinwood High School was about 90% Black and 10% White. A little over ten years earlier those numbers were reversed and during the transition from majority White to majority Black the school gained a reputation for racial confrontations and violence. Very, very few of my White classmates over the years from Bratenahl made the transition to the Cleveland Public School District. Most chose to attend nearby Catholic parochial schools.

I spent two years at Collinwood High School and graduated in 1983. My time there wasn’t without incident, including racially motivated altercations, but all in all my experience there was a great positive, in my view. In some of my classes, I was the only White student and at most there was two or three White students. Often during the school day I was the only White student walking the packed school halls. But it was ok. I experienced in some ways the same thing as the little Black boy I had met on my first day in first grade at Bratenahl Elementary School. I had become “the other.”

When I think back on the animosity faced by those Black students and their family members and friends as the Cleveland Public Schools only recently desegregated, I find it surprising that I faced so little blowback. The overwhelming lesson I learned from the experience of going to Collinwood High School and being in those circumstances a minority was that people are people. Certainly, different people have different ways of talking, different styles, different tastes in music, different histories, within what appear to be distinct groupings as well as between groupings. But Collinwood’s Black student body was no monolith and the same diversity you’d find in any other school was present there. To use the jargon of the time, the student body had its share of “jocks” and “nerds.” There were students, both Black and White, that came to school to cause trouble, but most of the students were not much different from high schools across the country for decades. Some where there because they wanted to be, some because they had to be, and some barely came at all. Some came for sports, some for academics, some for band or music, some just to socialize, a wide range of reasons. Just like any other high school.

Since my school days at Collinwood High School, I’ve often cringed when I heard people use gross generalizations about Black people and White people, pro or con, as if Black people and White people were a monolith. Black people are not a monolith and neither are White people. Some of the negative stereotypes that were common when I was a kid were “Black people are lazy” or “Black people are violent.” Some of the positive stereotypes were “Black people are athletic” or “Black people are musical.” None of those stereotypes had much resonance with me after going to Collinwood. I knew personally Black students who were very hard working, and who were lazy, who went out of their way to deescalate potentially violent situations, and who were only interested in starting trouble. I also knew plenty of Black kids that were anything but athletic or musical. The stereotypes and generalizations about Black people just didn’t hold up when I was emersed in an overwhelmingly Black high school population. Unfortunately, such a realization did not immunize me from having racial stereotypes creep into my own perceptions at times over the years.

The problem with White people and Black people is not so much inherent within White people or Black people themselves but the idea that the gross generalizations and stereotypes that such terms imply approximate reality, or are useful in describing reality. The terms “White people” and “Black people” and the attitudes that give rise to use of such term are much of the problem. There are two main problems, as I see it, with these terms. The first problem is defining who is encompassed by the terms and the second is finding an objectively useful purpose for the terms “White people” and “Black people.” Do these terms enlighten our understanding or confuse the issues? Do the terms help to free our minds from or ingrain into our minds stereotypes?

There may have been a time in our collective history when the terms White people and Black people actually did have some descriptive value. In the Antebellum South, the slave States prior to the Civil War, the terms had some resonance if only because people were divided under the law based on the color of their skin and ancestry. Although the White population had some diversity, with Irish, Jewish, German, Dutch, Spanish, etc. present, the vast majority of the White population was English, Scot-Irish, or Scottish. The White population was much more homogenous than today.

The Black population was fairly homogenous as well, with the vast majority being brought from West Africa as slaves, although the areas from which they were brought from was likely broader than thought in the past and the number of “mixed race” children larger than imagined. Over a hundred and fifty years later those fairly distinct groupings of Black and White just don’t have the same descriptive value.

Although the vast majority of those who consider themselves Black in America can trace their ancestry back to slaves, that does not mean that the makeup of the Black population in the United States has not drastically changed over the last 150 plus years since legal slavery ended. Blacks, like Whites, have intermixed with every constituent ethnicity of those labelled White as well as with Native Americans and every other grouping that has made America home. The contrast between Black and White in the Antebellum South has gotten blurred over time and will only get more and more blurred into the future.

One notable example of an African-American not being a descendent of slaves is the 44th President of the United States, Barrack Obama. President Obama is not the descendant of African slaves in America but the child of a Kenyan father who studied in the States in the early 1960’s and an American mother of primarily English ancestry. What heritage does he inherit?

As to those who consider themselves or are labeled White the difference between the population in the Antebellum South and today is perhaps even more stark. Since the end of the Civil War the United States has seen vast waves of immigrants who are labeled as White but are very distinct from the White populations in the Old South or the rest of the United States prior to the Civil War. Large numbers of Irish, Germans, Jews of various nationalities, Slavs, Scandinavians, Italians, peoples from the Baltics and Balkans, and from countless other smaller groups have been added to the mix. The ancestral homes of America’s White population is exponentially larger and more diverse than it was 150 plus years ago.

Included in this mix in ever increasing numbers are Whites Hispanics, themselves mainly the descendants of Spaniards who originally settled in Central and South America and intermixed in many cases to a certain extent with indigenous peoples. These peoples too have various histories and cultures very distinct from that of the “White” people of the Antebellum South.

Another 150 years from now what will White America and Black America look like, and will use of such terms be as common as they have been in the past or are now? My thought is that the distinctions and descriptive value of the terms Black and White will only continue to lessen and hopefully the terms will fade into the past. Certainly, some segments of the population, Black and White, or neither Black nor White, will work to keep such distinctions and divisions relevant. I have doubts about how successful they will be and toward what purpose such efforts are expended. The world is a complex place and the human race is hardly Black and White.