When I was in seventh or eighth grade in the late 1970’s I discovered a copy of the rock group The Doors first album, also title The Doors, that my older brothers had. I was hooked. The Doors were very popular from the release of their biggest hit Light My Fire in 1967 until the death of their lead singer, Jim Morrison, in Paris in July of 1971. The Doors broke up a few years later.

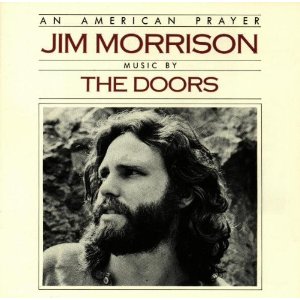

In 1978, the three surviving members of the group reunited and released the band’s final studio album, An American Prayer. An American Prayer never rose too high on the US charts, peaking at number 54, but it still stands as a unique outlier in commercially released music in America. I listened to An American Prayer probably over a hundred times when I was in high school but hadn’t for many, many years, until recently.

The genesis of An American Prayer was very unusual. While Morrison was still performing as the front man of The Doors he recorded a number of his poems without his bandmates in two studio sessions in 1969 and 1970 in Hollywood and West Los Angeles. Morrison had made tentative arrangements to craft the recordings into an album before his untimely death.

The release of An American Prayer heralded a resurgence of interest around the band and their late lead singer. In 1979, one of Morrison’s UCLA film school classmates, Francis Ford Coppola, used the beautiful and lyrical epic song The End from that debut album in his movie set during the Vietnam War, Apocalypse Now. In 1980 a very profitable and deeply flawed biography of Morrison came out titled “No One Here Gets Out Alive.” A year later the forever self-important Rolling Stone Magazine tried to jump on the popularity of Jim Morrison and The Doors with a cover photo of the singer on the tenth anniversary of his death with the headline, “Jim Morrison: He’s hot, he’s sexy, and he’s dead.” Another ten years and Oliver Stone again tried to monetize the legend of Jim Morrison with his movie, The Doors.

But An American Prayer was more about Morrison the poetic visionary than Morrison the sexy rock God. Morrison’s influences as a poet and performer went well beyond popular music, or even the early blues and country musicians that influenced so many of his contemporaries. The band The Doors took their name from a few lines from the English poet and printmaker William Blake’s poem, Marriage of Heaven and Hell, from the late 1700’s.

If the doors of perception were cleansed ever thing would appear to man as it is, Infinite. For man has closed himself up, till he sees all things thro’ narrow chinks of his cavern.

Another verse from Blake from The Marriage of Heaven and Hell in a section called Proverbs of Hell, is often associated with Morrison and his lifestyle. “The road of excess leads to the palace of wisdom.”

Morrison was also an avid student of the German philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche who wrote in 1888 in his book of aphorisms, Twilight of the Idols, “Out of life’s school of war—what doesn’t kill me, makes me stronger.” Both thoughts, the road to excess leading to the palace of wisdom and what doesn’t kill me makes me stronger, would doom Morrison’s poetic genius to an early demise.

As stated above, the album An American Prayer came into being when the three surviving members of The Doors, Robbie Krieger, Ray Manzarik, and John Densmore, reunited with studio engineer John Haney and others for the express purpose of crafting Morrison’s rough recordings into a finished album. As such, we can’t be certain that the final product would be exactly what Morrison wanted. In fact, we can be certain An American Prayer isn’t what Morrison himself would have produced. But we can feel confident that the musicians and musical professionals who knew his musical inclinations and artistic tendencies best and cared about Morrison’s legacy most helped craft the work in his absence.

What follows is my personal impressions of An American Prayer. This missive is not intended to be exhaustive or definitive, but personal. I would encourage anyone interested to read and listen to the album themselves if they are so inspired. Some may not be able to move past Morrison’s at times crude language and imagery, but for a few at least An American Prayer may be of some value.

In revisiting “An American Prayer” now, especially in light of my own journey these last 30 plus years, the spiritual longing I find in Morrison’s words is what stuck me most. From the very first stanzas of the title track:

Do you know the warm progress under the stars?

Do you know we exist?

Have you forgotten the keys to the kingdom

Have you been borne yet and are you alive?

Let’s reinvent the gods, all the myths of the ages

Celebrate symbols from deep elder forests

Have you forgotten the lessons of the ancient war

We need great golden copulations

Morrison was clearly on a spiritual journey, and he was looking to the past to find his way into the future. He speaks of his desire to “reinvent the gods,” “deep elder forests,” and the “lessons of the ancient war.” For what purpose? Morrison makes his plea a little later.

O great creator of being grant us one more hour

To perform our art and perfect our lives

Morrison’s revisits the same theme later on:

We have assembled inside,

This ancient and insane theater

To propagate our lust for life,

And flee the swarming wisdom of the streets.

Jim Morrison An American Prayer extended – YouTube

Morrison suffered the spiritual abyss in the world he was living in. Perhaps Morrison felt he was living in the world Nietzsche described in his aphorism The Madman. Nietzsche’s Madman regales stunned on lookers with his proclamation, “God is dead. God remains dead. And we have killed him.” The Madman then asked a series of questions that go to the heart of the questions I feel Morrison was trying to answer:

How shall we comfort ourselves, the murderers of all murderers? What was holiest and mightiest of all that the world has yet owned has bled to death under our knives: who will wipe this blood off us? What water is there for us to clean ourselves? What festivals of atonement, what sacred games shall we have to invent?

PHIL304-4.3.2-ParableoftheMadman.pdf

Morrison was trying in his own way to find a way back to God, the Great Creator of Being. Many may have assumed that Morrison was an atheist, or at best agnostic. Well known to fans of The Doors is Morrison’s opening lines in their epic song The Soft Parade, released about the same time the recordings for An American Prayer were made.

When I was back there in seminary school

There was a person there who put forth the proposition

That you can petition the Lord with prayer

Petition the lord with prayer

Petition the lord with prayer

You cannot petition the lord with prayer

Can you give me sanctuary

I must find a place to hide

A place for me to hide

Can you find me soft asylum

I can’t make it anymore

The Man is at the door

Reading Morrison’s words does not convey what his voice does though. Morrison’s voice in the first six lines is aggressive, arrogant, authoritarian. He deridingly repeats the religious propositions taught to him in seminary school. Whether that seminary school was literal or figurative, we don’t know. But Morrison spits out the words contemptuously as he mockingly screams at the listener, “You cannot petition the lord with prayer!” My own impression is that here he is mimicking his seminary teacher, real or imagined.

In the words that immediately follow those, though, Morrison’s voice has totally changed. He is now meek. He is humbly, plaintively pleading for sanctuary and “soft asylum.” From what is he seeking sanctuary? From whom is he hiding? Who is the man at the door?

I think Morrison would have agreed with another famous quote from Nietzsche’s book The Anti-Christ, “In truth there was only one Christian, and he died on the cross.” Many wrongly assume that Nietzsche had contempt or even a hatred for Jesus of Nazareth. This is a wrong interpretation of what Nietzsche was speaking to. Nietzsche spoke highly of Christ, but was derisive of the Christianity he saw practiced around him.

In An American Prayer’s poem, Newborn Awakening, Morrison speaks quite differently about prayer.

I called you up to

Annoint the earth

I called you to announce

Sadness falling like

Burned skin

I called you to wish you well

To glory in self like a new monster

And now I call on you to pray

Who are those who are being called up to anoint the earth and to pray? Morrison had a particular affinity for Native Americans and shamanism. He would tell a story, maybe apocryphal, about his family witnessing the aftermath of a car accident when he was quite young which resulted in a number of Native Americans lying dead in the road, one of whose soul jumped into his body.

Indians scattered on dawn’s highway bleeding

Ghosts crowd the young child’s fragile egg-shell mind

Morrison comes back to this image later.

Indian, Indian

What did you die for?

Indian says nothing at all

In addition to Native American, Morrison speaks of the “Blood in the streets of the town of New Haven.” A year or two before this poem was recorded, in the summer of 1967, “race riots” had broken out in New Haven after a White restaurant owner shot a Puerto Rican man. No one died but the city was rocked by arson, vandalism and looting, much like other cities in the United States that exploded in the 1960’s due to racial divisions and discrimination. More than a bit of irony to choose the town of New Haven as opposed to one of the many other cities across the country that suffered the same fate. A haven is of course a place of refuge or sanctuary. Was the town of New Haven a new haven for the people that migrated and immigrated there post World War II?

Morrison also alludes to our nation’s history of racial discrimination when he says, “Blood will be born in the birth of a nation.” As a former film school student, Morrison would have known of “Birth of a Nation,” D.W. Griffith’s 1915 silent film, originally titled The Clansman, as in the Ku Klux Klan. This film is widely considered both a breakthrough in the cinematic arts and one of the most blatantly racist widely distributed movies ever made in the land of the free. Birth of a Nation was the first full length film ever shown in the White House, having been screened by Democratic President Woodrow Wilson and his family.

Wow, I’m sick of doubt

Live in the light of certain south

Cruel bindings

I could give example after example of Morrison speaking sympathetically of those who lived in the shadows in America. He saw the unfulfilled promise of the New World as a refuge for the peoples of the world seeking freedom, and he wanted in his own small way to help that promise be realized. Morrison wanted to escape the “white free protestant maelstrom.”

Each color connects

to create the boat

which rocks the race

Morrison’s spiritual longing was toward perfecting our lives in the here and now. He was looking for the Great Creator Being to help in this life, not just to get him to the next life.

I’ll tell you this…

No eternal reward will forgive us now

For wasting the dawn

How did Morrison seek to answer the question which Nietzsche’s Madman asked, “How shall we comfort ourselves, the murderers of all murderers?” Perhaps at times through the use of consciousness altering substances, including prodigious amounts of alcohol.

Let me tell you about heartache and the loss of god

Wandering, wandering in hopeless night

Out here in the perimeter there are no stars

Out here we IS stoned

Immaculate

Jim Morrison – Stoned Immaculate (The poem). – YouTube

By all accounts Morrison did try to follow the Road of Excess to the Place of Wisdom. I think he knew, though, that the Road of Excess was a dead end as well:

Where are the feasts we are promised

Where is the wine

The New Wine

Dying on the vine

In the end, Morrison was just looking for something to believe in, a cause to give his life to.

Give us a creed

To believe

A night of Lust

Give us trust in

The Night

The lust here is not simple minded sexual desire, but as Morrison said before, he pleaded for all of us “to propagate our lust for life” and “flee the swarming wisdom of the streets.” In a poem not included in the original album An American Prayer, a poem called The American Night, Morrison reflected on his own accomplishments as a rock and roll singer, which included much fame and fortune and opportunities for satisfying any hedonistic desire he may have conjured:

I’ve done nothing w/time.

A little tot prancing the boards playing w/Revolution.

When out there the

World awaits & abounds w/heavy gangs of murderers & real madmen.

The American Night by Jim Morrison – Hello Poetry

Morrison was looking to be more than a showman, a carnival sideshow attraction, or to lead the life of a mindless hedonist. He was looking beyond all those things that accompany fame and fortune for meaning in his life. Morrison was looking for more than 1967’s summer of love and the “bloody red sun of phantastic L.A.” Such illusions do not give meaning to one’s life.

I don’t know if Morrison ever read the poet Georg Philipp Friedrich Freiherr von Hardenberg, more commonly known as Novalis. Novalis was a minor German aristocrat who lived in the late 1700’s and also wrote poetry. I think Morrison would have agreed with this verse of Novalis. “With the Ancients Religion certainly was what it should be with us—practical Poetry.” Like Morrison, Novalis died way too young at age 28, to Morrison’s 27. But his legacy grew larger and he was appreciated much more after his death, not unlike another of Morrison’s favorites, the French poet Arthur Rimbaud. As Nietzsche wrote, “Some men are born posthumously.”

An American Prayer was worth revisiting, unlike so much of the “content” which crowds our world today. Seems from a different age and time completely, but then it always has. Jim Morrison gave voice to a prayer for America worth listening to.